Letter 99

(99) GURU SWARUPAM (THE GURU’S FORM)

Prev Next

26th February, 1947

This afternoon a Tamil youth approached Bhagavan, and asked, “Swamiji! Yesterday morning you told the Gujarati lady that renunciation means internal renunciation. How are we to attain it? What is internal renunciation?”

Bhagavan: Internal renunciation means that all vasanas should be subdued. If you ask me, ‘How to attain that?’ my reply is, ‘it is attainable by sadhana.’

Question: Sadhana requires a Guru, doesn’t it?

Bhagavan: Yes! A Guru is required.

Question: How is one to decide upon a proper Guru? What is the swarupa of a Guru? Bhagavan: He is the proper Guru to whom your mind is attuned. If you ask, how to decide who is the Guru and what is his swarupa, he should be endowed with tranquillity, patience, forgiveness and other virtues capable of attracting others, even by a mere look, like the magnetic stone, and with a feeling of equality towards all --- he that has these virtues is the true Guru. If one wants to know the true Guru swarupa, one must know his own swarupa first. How can one know the true Guru swarupa, if one does not know one’s own swarupa first? If you want to perceive the true Guru swarupa, you must first learn to look upon the whole universe as Guru rupam. One must have the Gurubhavam towards all living beings. It is the same with God. You must look upon all objects as God’s rupa. How can he who does not know his own Self perceive Ishwara rupa or Guru rupa? How can he determine them? Therefore, first of all know your own real swarupam.

Question: Isn’t a Guru necessary to know even that?

Bhagavan: That is true. The world contains many great men. Look upon him as your Guru with whom your mind gets attuned. The one in whom you have faith is your Guru.

The youth was not satisfied. He started with a list of great men now living, and said, “He has that defect; he has this defect. How can they be looked upon as Gurus?” Bhagavan tolerates any amount of decrying of himself, but cannot tolerate even a little fault-finding of others. He said with some impatience, “Oho! you have been asked to know your own self, but instead you have started finding fault with others. It is enough if you correct your own faults.

Those people can take care of their faults. It looks as if they cannot attain salvation unless they obtain your certificate first.

That is a great pity! They are all waiting for your certificate.

You are a great man. Have they any salvation unless you approve of them? Here you blame them, elsewhere you will blame us. You know everything, whereas we know nothing, and we have to be submissive towards you. Yes! we shall do so. You go and please proclaim, ‘I went to Ramanasramam; I asked the Maharshi some questions; he was unable to reply properly, so he does not know anything’.” The youth was about to speak again in the same strain, but another devotee prevented him from doing so. Bhagavan observed it, and said, “Why do you stop him? Let all keep silent, and let him go on speaking as long as he pleases. He is a wise man. We must therefore lie low. I have been observing him ever since his arrival. He was originally sitting in a corner with all his questions carefully assorted and kept ready bundled up, as it were. He has since been moving and coming nearer day by day till at last he has come close enough and has started asking questions. After hearing the lady questioning me yesterday, he decided to show off his knowledge and so has opened his bundle. All that is in it must come out, mustn’t it? He is going to search the whole world and decide the Guru swarupa for himself. It seems he has not so far found anybody with the requisite qualifications for being his Guru. Dattatreya is the universal Guru, isn’t he? And he has said that the whole world was his Guru. If you look at evil you feel you should not do it. So he said evil also was his Guru. If you see good, you would wish to do it; so he said that good also was his Guru; both good and evil, he said, were his Gurus. It seems that he asked a hunter which way he should go, but the latter ignored his question, as he was intent upon his aim to shoot a bird above. Dattatreya saluted him, saying, ‘You are my Guru! Though killing the bird is bad, keeping your aim so steadfast in shooting the arrow as to ignore my query is good, thereby teaching me that I should keep my mind steadfast and fixed on Ishwara. You are therefore my Guru.’ In the same way he looked upon everything as his Guru, till in the end he said that his physical body itself was a Guru, as its consciousness does not exist during sleep and the body that does not existshould therefore not be confused with the soul --- dehatmabhavana (the feeling that the body is the soul). Therefore that too was a Guru for him. While he looked upon the whole world as his Guru, the whole world worshipped him as its Guru. It is the same with Ishwara. He who looks upon the whole universe as Ishwara, is himself worshipped by the universe as Ishwara --- yadbhavam tadbhavathi (‘as you conceive you become’) What we are, so is the world. There is a big garden. When a cuckoo comes to the garden it will search the mango tree for fruit while the crow will only search the neem tree. The bee searches for flowers to gather honey, while the flies search for the faeces. He who searches for the salagrama (small holy stone) will pick it up, pushing aside all the other stones. That salagrama is in the midst of a heap of ordinary stones. The good is recognised because evil also coexists. Light shines because darkness exists. Ishwara is there, only if illusion exists. He who seeks the essence, is satisfied if he finds one good thing among a hundred. He rejects the ninety-nine and accepts the one that is good, feeling satisfied that with that one thing he could conquer the world. His eye will always be on that single good thing.” Bhagavan said all this in a resounding voice and then remained silent.

The whole hall was steeped in a dignified silence. The clock struck four. As though it were the original peacock that had come to salute the lotus feet of the Arunachala Ramana that destroyed the demon Surapadma, and to offer praises to him, the Ashram peacock entered the hall from the northern side and announced its arrival by giving out a resounding cry. Bhagavan responded to the cry by saying, “Aav, Aav” (come, come) and turned his look that side.

Letter 98

(98) SELF (ATMAN)

Prev Next

25th February, 1947

This morning a Gujarati lady arrived from Bombay with her husband and children. She was middle-aged, and from her bearing she appeared to be a cultured lady. The husband wore khaddar, and appeared to be a congressman. They seemed to be respectable people by the way they conducted themselves.

They all gathered in the Hall by about 10 a.m., after finishing their bath, etc. From their attitude it could be seen that they intended to ask some questions. Within fifteen minutes or so they began asking as follows:

Lady: Bhagavan! How can one attain the Self?

Bhagavan: Why should you attain the Self?

Lady: For shanti (peace).

Bhagavan: So! Is that it? Then there is what is called peace, is there?

Lady: Yes! there is.

Bhagavan: All right! And you know that you should attain it. How do you know? To know that, you must have experienced it at some time or other. It is only when one knows that sugarcane is sweet, that one wishes to have some.

Similarly, you must have experienced peace. You experience it now and then. Otherwise, why this longing for peace? In fact we find every human being is longing similarly for peace; peace of some kind. It is therefore obvious that peace is the real thing, the reality; call that ‘shanti’, ‘soul’, or ‘Paramatma’ or ‘Self’ — whatever you like. We all want it, don’t we?

Lady: Yes! But how to attain it?

Bhagavan: What you have got is shanti itself. What can I say if some one asks for something which he has already got? If it is anything to be brought from somewhere, effort is required.

The mind with all its activities has come between you and your Self. What you have to do now is to get rid of that.

Lady: Is living in seclusion necessary for sadhana, or is it enough if we merely discard all worldly pleasures?

Bhagavan merely answered the second part of the question by saying, “renunciation means internal renunciation and not external,” and kept silent.

The dinner gong sounded from the dining hall.

What can Bhagavan reply to the earlier part of the last question of this lady who has a large family? She is also educated and cultured. Bhagavan used to speak similarly to householders; and there is a ring of appropriateness about it. After all, is internal or mental renunciation so easy as all that? That is why Bhagavan merely replied that renunciation means internal renunciation and not external.

Perhaps the next question would have been, “what is meant by ‘internal renunciation’?” and there would have been a reply if the dinner gong had not intervened. I returned to my abode where I live in seclusion. You see God has allotted to each individual what is apt and appropriate.

Did Bhagavan ever ask me, “Why are you living alone?” Or did he mention it to anybody else? Never. If you ask why, it is because this is appropriate to the conditions of my life.

Letter 97

(97) BIRTH

Prev Next

24th February, 1947

Yesterday a lady devotee showed Bhagavan her notebook in which she had copied out the five verses of “Ekatma Panchakam”. Bhagavan saw in that notebook two verses composed by him for his devotees when they first started celebrating his birthday, and told us the following incident:

“On one of my birthdays while I was in Virupaksha Cave, probably in 1912, those around me insisted on cooking food and eating it there as a celebration of the occasion. I tried to dissuade them, but they rebelled saying, ‘What harm does it do to Swamiji if we cook our food and eat it here?’ I therefore left it at that. Immediately after that they purchased some vessels. Those vessels are still here. What began as a small function has resulted in all this paraphernalia and pomp. Everything must take its own course and will not stop at our request. I told them at great length, but they did not listen. When the cooking and eating were over, Iswaraswamy who used to be with me in those days, said, ‘Swamiji! this is your birthday. Please compose two verses and I too will compose two.’ It was then that I composed these two verses which I find in the notebook here. They run as follows:

“This is the purport of those verses. It appears that it is a custom amongst a certain section of people in Malabar to weep when a child is born in the house and celebrate a death with pomp. Really one should lament having left one’s real state, and taken birth again in this world, and not celebrate it as a festive occasion.”

I asked, “But what did Iswaraswamy write?”

“Oh! He! He wrote, praising me as an Avatar (incarnation of God) and all that. That was a pastime with him in those days. He used to compose one verse and in return I used to compose one, and so on. We wrote many verses, but nobody took the trouble to preserve them. Most of the time we two were alone in those days; there were no facilities for food etc. Who would stay? Nowadays as all facilities are provided, many people gather around me and sit here. But what was there in those days? If any visitors came, they used to stay for a little while, and then go away. That was all.” On my request to give me a Telugu translation of those birthday verses, he wrote one and gave it to me.

Prev Next

24th February, 1947

Yesterday a lady devotee showed Bhagavan her notebook in which she had copied out the five verses of “Ekatma Panchakam”. Bhagavan saw in that notebook two verses composed by him for his devotees when they first started celebrating his birthday, and told us the following incident:

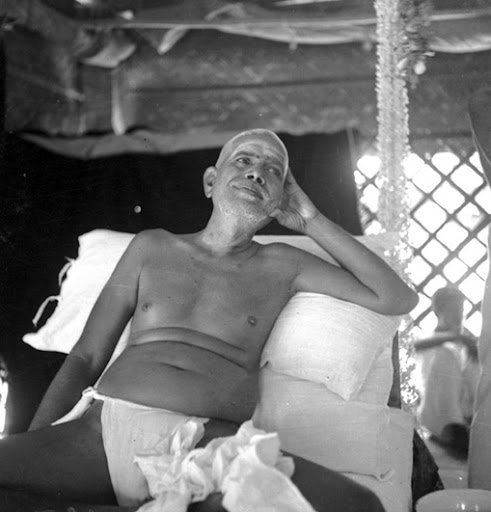

Photo (c) Sri Ramanasramam

“On one of my birthdays while I was in Virupaksha Cave, probably in 1912, those around me insisted on cooking food and eating it there as a celebration of the occasion. I tried to dissuade them, but they rebelled saying, ‘What harm does it do to Swamiji if we cook our food and eat it here?’ I therefore left it at that. Immediately after that they purchased some vessels. Those vessels are still here. What began as a small function has resulted in all this paraphernalia and pomp. Everything must take its own course and will not stop at our request. I told them at great length, but they did not listen. When the cooking and eating were over, Iswaraswamy who used to be with me in those days, said, ‘Swamiji! this is your birthday. Please compose two verses and I too will compose two.’ It was then that I composed these two verses which I find in the notebook here. They run as follows:

1. You who intend to celebrate the birthday, first ascertain as to whence you were born. The day that we attain a place in that everlasting life which is beyond the reach of births and deaths is our real birthday.

2. Even on these birthdays that occur once a year, we ought to lament that we have got this body and fallen into this world. Instead we celebrate the event with a feast. To rejoice over it is like decorating a corpse. Wisdom consists in realising the Self and in getting absorbed therein.

“This is the purport of those verses. It appears that it is a custom amongst a certain section of people in Malabar to weep when a child is born in the house and celebrate a death with pomp. Really one should lament having left one’s real state, and taken birth again in this world, and not celebrate it as a festive occasion.”

I asked, “But what did Iswaraswamy write?”

“Oh! He! He wrote, praising me as an Avatar (incarnation of God) and all that. That was a pastime with him in those days. He used to compose one verse and in return I used to compose one, and so on. We wrote many verses, but nobody took the trouble to preserve them. Most of the time we two were alone in those days; there were no facilities for food etc. Who would stay? Nowadays as all facilities are provided, many people gather around me and sit here. But what was there in those days? If any visitors came, they used to stay for a little while, and then go away. That was all.” On my request to give me a Telugu translation of those birthday verses, he wrote one and gave it to me.

Letter 96

(96) EKATMA PANCHAKAM

Prev Next

20th February, 1947

In my last letter I wrote to you about Telugu venba. I felt that it would have been better if Bhagavan had composed some more verses, but kept quiet for the time being, as I felt I should not ask unless a suitable opportunity presented itself. When I reached the hall in the afternoon of the 16th, Bhagavan was talking to a devotee about venba metre. He saw me and began to explain the differences between Tamil and Telugu chandas and said, “It seems once Guha Namasivaya Swamy decided to compose at the rate of one venba per day. That would be about 360 verses in a year. He composed a number of verses accordingly, some had been lost and the remaining verses were printed by his devotees. Quite a number of them are available now.” “Will it not be beneficial to the world if Bhagavan also composes similarly?” said the devotees.

“I do not know why, but my mind refuses to move in that direction. What am I to do?” replied Bhagavan.

“But they are so few! If some more are composed, and if the relative chandas is constructed, it will be a new treasure for our language!” I said.

“That is all very well, but am I a pandit? If all this is to be written, one has to study Bhagavatam, Bharatam and all that. But what am I to write about? What is there to write about?” he asked.

“Whatever Bhagavan writes will itself be a matter of interest,” I replied.

He replied, “You write so many verses. Is that not enough? If you want, get me Pedda Bala Siksha (popular children’s primer in Telugu), or Sulakshana Saram. I shall tell you the ganas, and you may compose yourself.”

I said, “I don’t want to write anything. If Bhagavan writes anything, I shall read it; otherwise not.” He laughed and kept silent.

I went out and began writing something sitting in front of the verandah. But you see Bhagavan is full of kindness.

As soon as I left the hall, it seems he composed a venba and read it out to the devotees. He saw me in the evening as he was going out, looked at me and said, “Here is another venba I have just now composed. You may see it.” Overwhelmed with joy, I looked at it and kept it. Bhagavan translated it into Tamil and told Muruganar, “Am I well read in Telugu? That is why I try to avoid writing in Telugu, but she keeps on asking. I raised several objections but she did not agree. Therefore I had to write.”

“Bhagavan’s saying is destined to come out in this manner,” said Muruganar. It was 6 p.m. I came home saying I would copy it the next day. I went to the Hall next morning at 8 o’clock. On seeing him, Bhagavan said, “Here is another composed by me last night. They make five in all. They may be called ‘Atma Panchakam’! But Sankara has already composed something under the same name. Let us therefore call them ‘Ekatma Panchakam’. I have already numbered the verses. You may verify, and copy them out.” As instructed, I copied them out. On seeing me do that, several other devotees also copied them and got them by heart.

This afternoon a lady devotee sang the Ekatma Panchakam in the Hall. When she sang the third verse, commencing ‘thanalo thanuvunda’ Bhagavan looked at me and said, “See I gave this example of the cinema when I was in Virupaksha Cave, even before cinemas became popular. There were no cinemas in Sankara’s time. Therefore he gave the example, ‘viswam darpana drisyamana nagari’. He would not have given that example if there had been cinemas in his time. We have now got in the cinema a very easy example to give.”

Letter 95

(95) TELUGU VENBA

Prev Next

15th February, 1947

The magazine Thyagi published last month a review on the recently printed Tamil puranam called Tiruchuli. In the review they included three verses taken out from the book called, Thiruchuli Venba Andadhi, for purpose of comparison.

Encouraged by the Sarvadhikari, I wanted to read the review, and therefore took the magazine from Bhagavan about ten days ago.

The venba is poetry with double meanings. Since it is in praise of Bhuminatha (i.e. Siva) it is pleasant to hear it sung. I was seated in the hall, staring at the magazine. Bhagavan felt that I would not be able to understand it, and so gave me the gist of the three verses, as follows: “Bhuminatha is the name of the God in Thiruchuli temple, and Sahaya Valli the name of the Goddess; this local purana is included in Skanda Purana under the name of Tirisulapura Mahatmyam.

“‘O Bhuminatha! All the Gods in heaven praised you as a hero unaided, on the assumption that you achieved victory by your own powers, unaided by any one in the fight against Tripurasuras. But you are Ardhanareeswara, half-man and half-woman; so, what would you have achieved in the fight against Tripurasuras, if you had not been aided by the Goddess Sahaya Valli? The left side of your body is hers. Could you have stretched your bow without her aid?’ That is the meaning.

“‘You are immobile as you are in the form of a Mountain; without the aid of the Goddess Sakti (energy), what could you achieve? Therefore it is not true to say that you are a hero, unaided. You cannot achieve anything without the aid of our Sahaya Valli. That is the other meaning.

There are many other varieties of special meanings included in those writings,” said Bhagavan, in an ecstasy of devotion.

It appears that the book Venba Andadhi was received from the editors of the magazine on the next day. When I went to the Ashram in the afternoon at 2-30, Bhagavan told me that the book had been received.

As I took it up to see, Bhagavan told me laughingly, “Nayana started to compose venba in Sanskrit, but the prasa (metre) did not agree, and he left off as he found the metre to be more difficult than arya vritta. He himself said that it is Sukla Chandas. Lakshmana Sarma at first composed his verses ‘Unnathi Nalubadhi’ in Sanskrit in venba metre but the prasa and ganas were not right. I corrected only the mangala sloka.

Narasinga Rao composed it in Telugu but that too did not come out well.” “That is perhaps because there is no suitable metre in Telugu,” I suggested. “Yes! It is so! It is rather difficult.

I could have composed it, but somehow I did not do so.” I asked Bhagavan, rather regretfully, “Has Bhagavan stopped altogether composing in Telugu?” He replied, “You yourself can do so, if I tell you the ganas. Why should I?” “But I do not know even the ordinary chandas. How can I know this specialised variety? Even Nayana could not compose, you said.

If so who else can do it? Bhagavan himself must write.

Bhagavan’s compositions which are in the form of sutras are very pleasant, aren’t they? You must please favour us (with your composition),” I requested him earnestly. He did not utter a word, but remained silent. I felt dejected and went home with the book.

I could not attend the hall for three days. When I reached there on the fourth day, Bhagavan gave me bits of paper and said, “The other day we were talking about ‘venba’ in Telugu. The next day I composed these three verses in Telugu and then translated them into Tamil. See! They should be sung in Sankarabharana raga slowly, very slowly.” “You should give us some more verses on the same lines!” I requested him. He replied, “Enough! There is no suitable chandas in Telugu. People would laugh at it! There is not even a suitable topic to write about! They are all ordinary words.” “Bhagavan’s voice does not require any topic in particular. Whatever comes out of his mouth is a topic, and that is the Veda. If there is no suitable metre in Telugu, why does Bhagavan not create one?” I said.

Muruganar supported me, and said, “If Bhagavan composes now and then like this, it will become a volume in due course. If the Telugu language can get a new metre, is it not a great gain for it?” Bhagavan did not reply. I copied out the three venbas for my record.

Letter 94

(94) HRIDAYAM – SAHASRARAM

Prev Next

13th February, 1947

As verses written by Bhagavan in Tamil on different occasions are found scattered in different notebooks, we have been thinking for a long time past that they should all be collected together in one book, but somehow we have delayed the matter. Four or five days back I told Niranjanananda Swami about this, brought a notebook and began copying them enthusiastically, though my knowledge of Tamil is very limited.

When I asked Bhagavan in what books they are to be found, he said, “They must be in those big notebooks bearing numbers one, two and three. Please see,” and again, “Whenever anyone asked me, I used to write them out on small bits of paper and give them to them. They used to take them away. Some of them were noted down in these books and some were not. If all of them were here, there would by now have been a quite a lot. I wrote many more while l was on the hill. Some of them were thrown away. Who had the desire or the patience to preserve them? If you want them, you may gather them now.”

I felt pained that the Divine voice expressed in verses had not been preserved for future generations and had thus been wasted. I took up volume one, and found verses under the heading, “Bhagavan’s Compositions.” I asked him what those verses were and he replied: “When I was in Virupaksha Cave, Nayana came there once with a boy named Arunachala. He had studied up to the school’s final class. While Nayana and I were talking, the boy sat in a bush nearby. He somehow listened to our conversation and composed nine verses in English, giving the gist of what we were talking about. The verses were good and so I translated them into Tamil verses in ahaval metre.

They read like Telugu dwipada metre. The substance of the verses is as follows:

From the sun of Bhagavan’s face, the rays of his words start out and bestow glow and strength on the moon of Ganapathy Sastry’s (Nayana’s) face which in turn lights the faces of people like us.

“One thing more. Ganapathy Sastry used to say that Sahasrara is the source and the centre of all. The Heart is the support of Sahasrara, is it not? The Heart bestows light on the Sahasrara. I used to say that the Heart is the source of all and that the force that emerges out of the Heart shines in the Sahasrara. To include this idea, the verse suggests a double meaning that the Heart is the sun, the solar orb, and the Sahasrara is the moon.”

Letter 93

(93) SADHANA IN THE PRESENCE OF THE GURU

Prev Next

12th February, 1947

Today, I reached the hall at about 3 p.m. Bhagavan was at leisure, answering questions asked by some devotee. One of the questions was: “Swami, they say that japa and tapa performed in the presence of Bhagavan yield greater results than usual. If so, what about bad actions done in your presence?”

Bhagavan replied, “If good actions yield good results, bad actions must yield bad results. If the gift of a cow in Benares yields great punya (virtue) to the donor, the slaughter of a cow there result in great papa (sin). When you say that a little virtuous action done in a holy place yields enormous benefit, a sinful action must likewise yield enormous harm. So long as the feeling that you are the doer is there, you must face the consequences of your actions, good or bad.”

“There is the desire to discard bad habits but the force of the vasanas is very strong. What are we to do?” that person continued.

“There must be human effort to discard them. Good company, good contacts, good deeds and all such good practices must be acquired in order to eliminate the vasanas.

As you keep on trying, eventually with the ripening of the mind and with God’s grace, the vasanas get extinguished and efforts succeed. That is called purushakaram (human effort). How could God be expected to be favourable towards you without your striving for it?” said Bhagavan.

Another person took up the thread of conversation and said, “It is said that the whole universe is God’s chidvilasam and that everything is Brahmamayam. Then why should we say that bad habits and bad practices should be discarded?”

Bhagavan replied, “Why? I will tell you. There is the human body. Suppose there is some wound inside it. If you neglect it, on the assumption that it is only a small part of the body, it causes pain to the whole body. If it is not cured by ordinary treatment, the doctor must come, cut off the affected portion with a knife and remove the impure blood. If the diseased part is not cut off it will fester.

“If you do not bandage it after operation, puss will form.

It is the same thing with regard to conduct. Bad habits and bad conduct are like a wound in the body; if a man does not discard them, he will fall into the abyss below. Hence every disease must be given appropriate treatment.”

“Bhagavan says that sadhana must be done to discard all such bad things, but the mind itself is inert and cannot do anything by itself --- Chaitanya (Self) is achalam (motionless) and so will not do anything. Then how is one to perform sadhana?” someone asked.

Bhagavan replied, “Oho! But how are you able to talk now?”

“Swami, I do not understand that and that is why I ask for enlightenment,” he said.

Bhagavan replied, “All right. Then please listen. The mind which is inert is able to achieve everything by the force of its contact, sannidhyabala (strength of proximity) with chaitanya which is achala. But without the aid of chaitanya the inert mind cannot accomplish anything by itself. Chaitanya, being immobile, cannot accomplish anything without the help of the mind. It is the relationship of avinabhavam, one dependent on the other, and inseparable. That is why elders discussed this matter from various angles and came to the conclusion that the mind is chit-jada-atmakam. We have to say that the combination of chit (Self) and jada (inert) produces action.” Bhagavan has written nicely about this Chit-jada-granthi in his “Unnathi Nalubadhi”, verse 24, as follows: The body does not say ‘I’. The Atman is not born. In between, the feeling ‘I’ is born in the whole body.

Whatever name you give it that is Chit-jada-granthi (the knot between the consciousness and the inert), and also bondage.

Prev Next

12th February, 1947

Today, I reached the hall at about 3 p.m. Bhagavan was at leisure, answering questions asked by some devotee. One of the questions was: “Swami, they say that japa and tapa performed in the presence of Bhagavan yield greater results than usual. If so, what about bad actions done in your presence?”

Bhagavan replied, “If good actions yield good results, bad actions must yield bad results. If the gift of a cow in Benares yields great punya (virtue) to the donor, the slaughter of a cow there result in great papa (sin). When you say that a little virtuous action done in a holy place yields enormous benefit, a sinful action must likewise yield enormous harm. So long as the feeling that you are the doer is there, you must face the consequences of your actions, good or bad.”

“There is the desire to discard bad habits but the force of the vasanas is very strong. What are we to do?” that person continued.

“There must be human effort to discard them. Good company, good contacts, good deeds and all such good practices must be acquired in order to eliminate the vasanas.

As you keep on trying, eventually with the ripening of the mind and with God’s grace, the vasanas get extinguished and efforts succeed. That is called purushakaram (human effort). How could God be expected to be favourable towards you without your striving for it?” said Bhagavan.

Another person took up the thread of conversation and said, “It is said that the whole universe is God’s chidvilasam and that everything is Brahmamayam. Then why should we say that bad habits and bad practices should be discarded?”

Bhagavan replied, “Why? I will tell you. There is the human body. Suppose there is some wound inside it. If you neglect it, on the assumption that it is only a small part of the body, it causes pain to the whole body. If it is not cured by ordinary treatment, the doctor must come, cut off the affected portion with a knife and remove the impure blood. If the diseased part is not cut off it will fester.

“If you do not bandage it after operation, puss will form.

It is the same thing with regard to conduct. Bad habits and bad conduct are like a wound in the body; if a man does not discard them, he will fall into the abyss below. Hence every disease must be given appropriate treatment.”

“Bhagavan says that sadhana must be done to discard all such bad things, but the mind itself is inert and cannot do anything by itself --- Chaitanya (Self) is achalam (motionless) and so will not do anything. Then how is one to perform sadhana?” someone asked.

Bhagavan replied, “Oho! But how are you able to talk now?”

“Swami, I do not understand that and that is why I ask for enlightenment,” he said.

Bhagavan replied, “All right. Then please listen. The mind which is inert is able to achieve everything by the force of its contact, sannidhyabala (strength of proximity) with chaitanya which is achala. But without the aid of chaitanya the inert mind cannot accomplish anything by itself. Chaitanya, being immobile, cannot accomplish anything without the help of the mind. It is the relationship of avinabhavam, one dependent on the other, and inseparable. That is why elders discussed this matter from various angles and came to the conclusion that the mind is chit-jada-atmakam. We have to say that the combination of chit (Self) and jada (inert) produces action.” Bhagavan has written nicely about this Chit-jada-granthi in his “Unnathi Nalubadhi”, verse 24, as follows: The body does not say ‘I’. The Atman is not born. In between, the feeling ‘I’ is born in the whole body.

Whatever name you give it that is Chit-jada-granthi (the knot between the consciousness and the inert), and also bondage.

Letter 92

(92) AADARANA (REGARD)

Prev Next

10th February, 1947

At noon today three French ladies arrived here by car from Pondicherry. One was the Governor’s wife, another the Secretary’s wife and the third was someone connected with them. They rested for a while after food and reached the hall by about 2-30 p.m. Two of them could not sit on the floor and so they sat on the window sill opposite to Bhagavan; the third somehow managed to sit on the floor. They took leave of Bhagavan at about 3 p.m. and left. When I saw them I remembered some other incidents connected with the visit of an American lady to the Ashram, how she sat with legs stretched out, and was advised by the inmates of the Ashram not to do so, how Bhagavan admonished them by narrating the stories of Avaiyar and Namdev. I wrote to you about all that long back. I shall now write to you two more incidents of a similar type.

About ten months ago, an old European lady came here along with another European called Frydman and stayed here for about twenty days. She was not accustomed to squatting on the ground because of her Western style of living. Besides, she was old. So she used to suffer considerably, being unable to sit down, and if she sat down, she was finding it difficult to get up. The gentleman used to help her to get up, by holding her hand. One day when I reached the hall by about 8 a.m. I found them both seated in the front row in the space allotted for ladies. The other ladies were hesitating to sit nearby, and so I signalled to him to move a bit farther away, which he did immediately. Bhagavan got annoyed and looked at me but I did not at the time know why. I was standing near the sofa talking to somebody. Frydman suddenly got up and also helped her to get up. Her eyes were filled with tears and most reluctantly she took leave of Bhagavan. Bhagavan as usual nodded his head in token of permission. As soon as they left, Bhagavan looked at me and said, “It is a pity they are going away.” I felt that I had committed a great crime and said, “I am sorry. I did not know they were leaving.” Bhagavan felt that I had realised my mistake and that I was repenting for it and so said, “No. It is not that. They suffer a lot if they sit on the ground. That is why so many who are anxious to come here stay away. They are not accustomed to squat. What can they do? It is a great pity.” Some time ago, a very poor old lady came here one morning with her relatives. All except she made their pranams to Bhagavan and sat down. She however remained standing.

Krishnaswamy, the attendant, requested her to sit down, but she did not do so. Her relatives called her to come away but she did not do that either. l too advised her to go to them and sit down, but she did not take any notice. Someone there said, admonishing her, “Why don’t you listen to the advice of all the people here?” I looked at her relatives to find out the reason of her obstinacy. They said that she was almost blind and so wanted to go near Swami to see him at close quarters. I got up, took her hand and led her to the sofa where Bhagavan was seated. Shading her eyes with the palm of her hand she looked at Bhagavan intently and said, “Swami! I can’t see properly. Please bless me that I may be enabled to see you in my mind.” With looks full of tenderness, Bhagavan nodded his head by way of assent saying, “All right.” As soon as they left, Bhagavan told us, “The poor lady can’t see properly and so was afraid of coming near to see me. What can she do? She merely stood there. To those who have no eyes, the mind is the eye. They have only one sight, that of the mind, and not many other sights to distract their attention. Only the mind should get concentration.

When once that is obtained they are much better than us.” What a mild and soothing admonition!

Letter 91

(91) MAYA (ILLUSION)

Prev Next

9th February, 1947

The same devotee who questioned Bhagavan yesterday again asked him this afternoon about illusion, maya: “Swami, all the innumerable varieties of things that appear to the human mind to be real, are mere maya (illusion), aren’t they? Will the illusion disappear if they are all discarded?”

Bhagavan replied, “Illusion will continue to appear as illusion, so long as the idea that oneself and Ishwara are two different entities persists. When once that illusion is discarded and the individual realises that he is Ishwara, he will understand that maya is not something distinct and separate from his own self. Ishwara exists without and distinct from illusion, but there is no illusion without Ishwara.” “Therefore that illusion changes into pure illusion, doesn’t it?” asked the questioner. Bhagavan replied, “Yes! It amounts to that; unless the individual self is existent how can one realise Ishwara? There is no self, unless the illusion is there. When once the individual realises who he is, the evil effects, i.e., ‘doshas’ of illusion do not affect him. Call it pure illusion, or anything else you like. That is the essential thing.”

Somebody else took up the topic and asked, “They say that the jiva is subject to the evil effects of illusion such as limited vision and knowledge, whereas Ishwara has all- pervading vision and knowledge and such other characteristics and that jiva and Ishwara become one and identical if the individual discards his limited vision and knowledge, and such other characteristics usually attached to him. But should not Ishwara also discard his particular characteristics such as all-pervading vision and knowledge? They too are illusions, aren’t they?”

“Is that your doubt? First discard your limited vision and such like characteristics and then it will be time enough to think of Ishwara’s all-pervading vision, knowledge etc.

First get rid of your limited knowledge. Why do you worry about Ishwara? He will look after Himself. Has He not got as much capacity as we have? Why should we worry whether He possesses the all-pervading vision and knowledge or not? It is indeed a great thing if we can take care of ourselves.”

The questioner asked again, “But first of all we must find a Guru who can give us sufficient practice and thereby enable us to get rid of these gunas, mustn’t we?”

“If we have the earnestness to get rid of these qualities can we not find a Guru? We must first have the desire to get rid of them. When once we have this the Guru will himself come, searching for us, or he will somehow manage to draw us to himself. The Guru will always be on the alert and keep an eye on us; Ishwara Himself will show us the Guru. Who else will look after the welfare of the children except the father himself? He is always with us, surrounding us. He protects us, as a bird protects its eggs by hatching them under the shelter of its wings. But we must have whole-hearted faith in Him,” said Bhagavan.

A devotee, by name Sankaramma, who is generally afraid of asking Bhagavan questions, said quietly on hearing those words: “But Swamiji! Guru’s upadesa (instruction) is necessary for sadhana, isn’t it?” Bhagavan replied, “Oh! Is that so? But that upadesa is being given every day. Those who are in need of it, may have it.” Others present there said: “But Bhagavan must bless us that we may be enabled to receive the instruction. That is our prayer.”

“The blessing is always there,” replied Bhagavan.

Prev Next

9th February, 1947

The same devotee who questioned Bhagavan yesterday again asked him this afternoon about illusion, maya: “Swami, all the innumerable varieties of things that appear to the human mind to be real, are mere maya (illusion), aren’t they? Will the illusion disappear if they are all discarded?”

Bhagavan replied, “Illusion will continue to appear as illusion, so long as the idea that oneself and Ishwara are two different entities persists. When once that illusion is discarded and the individual realises that he is Ishwara, he will understand that maya is not something distinct and separate from his own self. Ishwara exists without and distinct from illusion, but there is no illusion without Ishwara.” “Therefore that illusion changes into pure illusion, doesn’t it?” asked the questioner. Bhagavan replied, “Yes! It amounts to that; unless the individual self is existent how can one realise Ishwara? There is no self, unless the illusion is there. When once the individual realises who he is, the evil effects, i.e., ‘doshas’ of illusion do not affect him. Call it pure illusion, or anything else you like. That is the essential thing.”

Somebody else took up the topic and asked, “They say that the jiva is subject to the evil effects of illusion such as limited vision and knowledge, whereas Ishwara has all- pervading vision and knowledge and such other characteristics and that jiva and Ishwara become one and identical if the individual discards his limited vision and knowledge, and such other characteristics usually attached to him. But should not Ishwara also discard his particular characteristics such as all-pervading vision and knowledge? They too are illusions, aren’t they?”

“Is that your doubt? First discard your limited vision and such like characteristics and then it will be time enough to think of Ishwara’s all-pervading vision, knowledge etc.

First get rid of your limited knowledge. Why do you worry about Ishwara? He will look after Himself. Has He not got as much capacity as we have? Why should we worry whether He possesses the all-pervading vision and knowledge or not? It is indeed a great thing if we can take care of ourselves.”

The questioner asked again, “But first of all we must find a Guru who can give us sufficient practice and thereby enable us to get rid of these gunas, mustn’t we?”

“If we have the earnestness to get rid of these qualities can we not find a Guru? We must first have the desire to get rid of them. When once we have this the Guru will himself come, searching for us, or he will somehow manage to draw us to himself. The Guru will always be on the alert and keep an eye on us; Ishwara Himself will show us the Guru. Who else will look after the welfare of the children except the father himself? He is always with us, surrounding us. He protects us, as a bird protects its eggs by hatching them under the shelter of its wings. But we must have whole-hearted faith in Him,” said Bhagavan.

A devotee, by name Sankaramma, who is generally afraid of asking Bhagavan questions, said quietly on hearing those words: “But Swamiji! Guru’s upadesa (instruction) is necessary for sadhana, isn’t it?” Bhagavan replied, “Oh! Is that so? But that upadesa is being given every day. Those who are in need of it, may have it.” Others present there said: “But Bhagavan must bless us that we may be enabled to receive the instruction. That is our prayer.”

“The blessing is always there,” replied Bhagavan.

Letter 90

(90) THE JNANI’S MIND IS BRAHMAN ITSELF

Prev Next

8th February, 1947

I went to the Hall at about 7-30 this morning. It was all silent inside. The aroma of the burning incense sticks coming out of the windows indicated to the new visitors that Bhagavan was there. I went inside, bowed before Bhagavan and then sat down. Bhagavan, who was all along leaning on a pillow, sat up erect in the Padmasana pose. In a moment his look became motionless and transcendent and the whole hall was filled with lustre. Suddenly someone asked, “Swamiji! Do the Jnanis have a mind or not?”

Bhagavan cast a benevolent look at him, and said, “There is no question of one realising Brahman without a mind; realisation is possible only if there is a mind; mind always functions with some upadhi (support); there is no mind without upadhi; it is only in connection with the upadhi that we say that one is a Jnani. Without the upadhi, how can one say that some one is a Jnani? But how does the upadhi function without mind? It does not; that is why it is said that the Jnani’s mind itself is Brahman. The Jnani is always looking at Brahman. How is it possible to see without a mind? That is why it is said that the Jnani’s mind is Brahmakara and akhandakara. But in reality his mind itself is Brahman. Just as an ignorant man does not recognise Brahman within but only recognises the external vrittis (things), so also though the Jnani’s body moves about in the external vrittis, he always recognises only the Brahman within. That Brahman is all- pervading. When once the mind is lost in the Brahman, to call the mind Brahmakara is like saying that a river is like the ocean; when once all the rivers get lost in the ocean, it is all one vast sheet of water. Can you then distinguish in that vast sheet of water, ‘This is the Ganges, this is the Goutami, this river is so long, that river is so wide’, and so on? It is the same with regard to the mind also.”

Someone else asked, “They say that satvam is Brahman, and that rajas and tamas are abhasa; is that so?” Bhagavan replied: “Yes! Sat is what exists; Sat is satvam; it is the natural thing; it is the subtle movement of the mind. By its contacts with rajas and tamas it creates the world with its innumerable forms. It is only due to its contact with rajas and tamas that the mind looks at the world which is abhasa, and gets deluded.

If you remove that contact, satva shines pure and uncontaminated. That is called pure Satva or Suddhasatva.

This contact cannot be eliminated unless you enquire with the subtlest of the subtle mind and reject it. All the vasanas have to be subdued and the mind has to become very subtle; that means, subtle among the subtlest --- they say anoraneeyam (atom within an atom). It should become atomic to the atom.

If it becomes subdued as an atom to the atom, then it rises to the infinite among infinities, ‘mahato maheeyam’. Call it the mind seeing, or the mind acquiring powers; call it whatever you like. By whatever name it is called, when we sleep the mind, with all its activities lies subdued in the heart. What do we see then? Nothing. Why? Because the mind lies subdued. We wake up from our sleep, and as soon as we wake up there is mind, there is Sat and Brahman. As soon as the mind that is awake is attached to the gunas, every activity emerges. If you discard those guna vikaras, (vagaries of the mind), the Brahman appears everywhere, self-luminous and self-evident, the Aham, ‘I’. Then everything appears thanmayam (all pervading). See the technical language of the Vedanta: they say, Brahma-vid, (Brahman-knowing), Brahma Vidvarishta, (supreme among the Brahman-knowing), and so on, and then they say, Brahmaiva Bhavati, (he becomes Brahman itself). He is Brahman itself. That is why we say that the jnani’s mind itself is Brahman.”

Someone else asked, “They say that the Jnani conducts himself with absolute equality towards all?” Bhagavan replied, “Yes! How does a Jnani conduct himself?”

Maitri (friendship), karuna (kindness), mudita (happiness) and upeksha (indifference) and such other bhavas become natural to them. Affection towards the good, kindness towards the helpless, happiness in doing good deeds, forgiveness towards the wicked, all such things are natural characteristics of the Jnani.

-- Patanjali Yoga Sutra, 1: 33

Letter 89

(89) THE INCARNATION OF SRI DAKSHINAMURTHY

Prev Next

7th February, 1947

While translating “Dakshinamurthy Stotram” into Tamil verse with commentary, Bhagavan summarised the original story about the reason for Dakshinamurthy’s incarnation and wrote it in the preface. Besides that he divided nine slokas therein into three groups dealing with the world, the seer and the seen respectively.

The first three:(1) Viswam Darpanam, (2) Bijasyanthariva, (3) Yasyaiva sphuranum, deal with the origin of the world.

The next three: (1) Nanachhidra, (2) Rahugrastha, (3) Deham Pranam, deal with the seer; and the last three: (1) Balyadishwapi (2) Viswam Pasyathi (3) Bhurambhamsi, deal with the light by which things are seen. The last sloka, Sarvathmatvam, means that the whole universe is merged in Brahman.

Recently I translated the preface into Telugu. Bhagavan went through the translation, and said with a smile, “I mentioned briefly in the preface, only as much of the life story as related to the stotra, but the real story is much more interesting. It goes like this: Brahma asked Sanaka, Sanatkumara, Sanandana and Sanatsujata, who are the creations of his mind, to assist him in the task of creation, but they were not interested in that task and so declined to assist. They were surrounded by the heavenly gods, saints and other attendants, and were staying in Nandana Vana and so they were considering who would impart to them jnana, the supreme Wisdom. Narada appeared, and said, ‘Who can impart the Brahma Jnana, the Supreme Wisdom, except Brahma himself? Come on, we shall go to him.’ They all agreed and proceeded to Satya Loka, the abode of Brahma, and found Saraswathi playing the veena, with Brahma seated in front of her, enjoying the music and beating time to the tune. They all beheld the scene and wondered how a person who is engrossed in the appreciation of his wife’s music could teach them adhyatma tattva (the essence of spirituality). Narada said to them, ‘Come! let us go to Vaikunta, the abode of Vishnu’. They all proceeded thither.

The Lord was in the interior of his residence. Narada is however a privileged person and so he went directly into the Lord’s abode, saying he would see and come back. Soon he came out and, when asked, told them, ‘There Brahma was seated a little away from his wife who was playing the veena for him. But here, the Goddess Lakshmi is seated on the God’s couch and is massaging his feet. This is much worse. How can this family man who is spellbound by the intimate glances of his consort, render us any help (in learning adhyatma vidya)? Look at the splendour of this palace and this city! This is no good. Let us seek the help of Lord Siva.’ “They all proceeded towards Himachala and seeing Mount Kailas, they ascended it with great hopes.

But there, in the midst of a vast gathering of his fellows, was Siva performing his celestial dance with his wife sharing half of his body. Vishnu was playing on the Drum, and Brahma was keeping time with the bells as an accompaniment for the dance. They who came eagerly seeking spiritual guidance, were aghast at the sight, and thought, ‘Oh! He too is after women! Brahma was no doubt having his wife sitting very close to, but was not in physical contact with her, while Vishnu was in physical contact with his wife, but she was merely massaging His legs, but Siva is actually keeping Parvati as part of His body. This is much worse. Enough of this.’ And they all departed.

Siva understood and was sorry for them. He said, ‘What delusion on their part! They regard the three Godheads as devoid of spiritual wisdom merely because they were being served by their respective wives at the time the devotees saw them! Who else can impart spiritual knowledge to these earnest seekers of Truth?’ Thus thinking, Siva sent away Parvati on the plea of himself doing tapas and the kind-hearted Lord seated Himself in the guise of a youth with Chinmudra, as Dakshinamurthy, under a banyan tree on the northern side of lake Mansarovar, just on the way by which these disappointed devotees were returning to their respective homes. I read this story somewhere,” said Bhagavan.

“How interesting is the story! Why did not Bhagavan include it in the Introduction?” I said.

“I cannot say! I thought it unnecessary for me to record all these incidents of Dakshinamurthy’s life in the Introduction. I included only as much as was required for the Ashtaka (8 slokas),” replied Bhagavan.

On further enquiry, it was found that this story was narrated in Siva Rahasya, tenth canto, second chapter, under the heading, “The Incarnation of Sri Dakshinamurthy.” A devotee who heard this asked, “Does incarnation mean birth of Sri Dakshinamurthy?” “Where is the question of a birth for him? It is one of the five Murthys (forms) of Siva. It means that he is seated facing south in mouna mudra (silent posture).

It is the want of Form, Formlessness, that is indicated in its inner meaning. Is it the Murthy, the Form, that is described in the “Dakshinamurthy Ashtaka”? Is it not the want of Form, Formlessness? ‘Sri Dakshinamurthy’ --- ‘Sri’ means Maya Sakti (illusory force); one meaning of ‘Dakshina’ is efficient; another meaning is ‘in the heart on the right side of the body’ ‘Amurthy’ means ‘Formlessness’. A lot of commentary on this is possible, isn’t it?” said Bhagavan.

The same devotee asked, “Sanaka and the others are described in the Bhagavata Purana as young boys of five years of age for all time; but this stotra says ‘vriddha sishya gurur yuva’ (old disciples and young Guru). How is that?” “Jnanis (the wise) always remain young. There is no youth, and no old age for them. The description ‘vriddha’ and ‘sishya’, ‘old’ and ‘disciple’ means that Sanaka and the others were old in actual age. Though they are old in years they remain everlastingly young in appearance,” said Bhagavan.

I give below my translation of the introduction written by Bhagavan: “Sanaka, Sanandana, Sanatkumara and Sanatsujata who are the four sons born from the mind of Brahma, learnt that they were brought into existence to further the creation of the world, but they were not interested in the task, and sought only Truth and Knowledge and wandered in search of a Guru. Lord Siva sympathised with those earnest seekers of Truth and Himself sat under a banyan tree in the silent state as Dakshinamurthy with chinmudra. Sanaka and the others observed Him and were at once attracted by Him like iron by a magnet, and attained Self-realisation in His presence in no time. To those who are not able to know the real significance of the silent and original form (of Dakshinamurthy), Sankara summarised the universal truth in this stotra and explained to Utamadhikaris (highly developed souls) that the Sakti (force) which dissolves the three obstacles for realisation of the Truth, that is the world, the seer and the seen, is not different from one’s own self and that everything gets ultimately merged in one’s own self.”

Related: Collected Works - Hymn to Dakshinamurthi, Talk 569.

Letter 88

(88) SLEEP AND THE REAL STATE

Prev Next

4th February, 1947

This afternoon somebody handed a slip of paper with a question on it to Bhagavan. The purport of it was: “What happens to this world during sleep? In what state is the Jnani during sleep?”

Affecting surprise, Bhagavan replied, “Oh! Is that what you want to know? Do you know what is happening to your body and in what state you are when you are asleep? During your sleep you forget that your body is here, in this place, on this mat, in this very condition, and you wander about somewhere and do something. It is only when you wake up that you realise that you are here. But you are always existent during the sleeping state as well as during the waking state. Your body is living inert, without any activity during your sleep. Therefore you are not this body during the sleeping condition. Then, to what are you attached during sleep? There must be something which is the prop for these comings and goings. You lie down with a view to sleep. But you get dreams; next you sleep, knowing happily nothing. It is a very happy sleep. So you admit that you were there in the sleeping state. And yet you say that you are aware of nothing in that state. What is real, you say you do not know. What is unreal and fleeting, you say you know. But in truth you know what is real. These fleeting things --- let them come and go --- they will not touch you.

You do not know about yourself but you ask what happens to the world? What does the Jnani experience in the sleeping state? If you first know what happens to you, the world will know about itself. You ask about Jnanis; they are the same in any state or condition, as they know the Reality, the Truth.

In their daily routine of taking food, moving about and all the rest, they, the Jnanis, act only for others. Not a single action is done for themselves. I have already told you many times that just as there are people whose profession is to mourn for a fee, so also the Jnanis do things for the sake of others with detachment, without themselves being affected by them.”

Another devotee took up the conversation and asked, “Swami, you say the real state must be known, and that meditation is necessary to realise that. But first of all what is meditation?”

“Meditation means Brahman,” Bhagavan replied. Continuing, he said, “To get rid of the evils that are created by the mind, it is said that some nishta (religious practice) must be adopted, and meditation based on that must be practised. As you go on doing it, those evils will disappear. And, after they disappear, the meditation itself becomes fixed as Brahman. Tapas also means the same thing.

When you ask how to get rid of all these vasanas, they say, ‘Do tapas.’ But what is the reward of tapas? It is said, ‘tapas itself is the reward.’ Tapas means swarupa (realisation of the Self). What is real is the swarupa, that is Atma, the Supreme Self, that is Brahman. That is everything. Of course in technical language you have to say. ‘Do meditation’ but these doubts do not arise if you know who it is that is really meditating.” The same idea is conveyed in Bhagavan’s “Upadesa Saram”:

Prev Next

4th February, 1947

This afternoon somebody handed a slip of paper with a question on it to Bhagavan. The purport of it was: “What happens to this world during sleep? In what state is the Jnani during sleep?”

Affecting surprise, Bhagavan replied, “Oh! Is that what you want to know? Do you know what is happening to your body and in what state you are when you are asleep? During your sleep you forget that your body is here, in this place, on this mat, in this very condition, and you wander about somewhere and do something. It is only when you wake up that you realise that you are here. But you are always existent during the sleeping state as well as during the waking state. Your body is living inert, without any activity during your sleep. Therefore you are not this body during the sleeping condition. Then, to what are you attached during sleep? There must be something which is the prop for these comings and goings. You lie down with a view to sleep. But you get dreams; next you sleep, knowing happily nothing. It is a very happy sleep. So you admit that you were there in the sleeping state. And yet you say that you are aware of nothing in that state. What is real, you say you do not know. What is unreal and fleeting, you say you know. But in truth you know what is real. These fleeting things --- let them come and go --- they will not touch you.

You do not know about yourself but you ask what happens to the world? What does the Jnani experience in the sleeping state? If you first know what happens to you, the world will know about itself. You ask about Jnanis; they are the same in any state or condition, as they know the Reality, the Truth.

In their daily routine of taking food, moving about and all the rest, they, the Jnanis, act only for others. Not a single action is done for themselves. I have already told you many times that just as there are people whose profession is to mourn for a fee, so also the Jnanis do things for the sake of others with detachment, without themselves being affected by them.”

Another devotee took up the conversation and asked, “Swami, you say the real state must be known, and that meditation is necessary to realise that. But first of all what is meditation?”

“Meditation means Brahman,” Bhagavan replied. Continuing, he said, “To get rid of the evils that are created by the mind, it is said that some nishta (religious practice) must be adopted, and meditation based on that must be practised. As you go on doing it, those evils will disappear. And, after they disappear, the meditation itself becomes fixed as Brahman. Tapas also means the same thing.

When you ask how to get rid of all these vasanas, they say, ‘Do tapas.’ But what is the reward of tapas? It is said, ‘tapas itself is the reward.’ Tapas means swarupa (realisation of the Self). What is real is the swarupa, that is Atma, the Supreme Self, that is Brahman. That is everything. Of course in technical language you have to say. ‘Do meditation’ but these doubts do not arise if you know who it is that is really meditating.” The same idea is conveyed in Bhagavan’s “Upadesa Saram”:

Ahamapetakam nijavibhaanakam

mahadidam tapo ramanavaagiyam

The Realisation of That which subsists when all trace of ‘I’ is gone is great tapas. So sings Ramana.

-- Upadesa Saram, verse 30

Letter 87

(87) DIVINE FORCE

Prev Next

2nd February, 1947

I went to the hall at 2-30 this afternoon. Bhagavan was there already, reading a slip of paper which someone had handed over to him. I sat there waiting to hear what Bhagavan would say. Bhagavan folded the paper with a smile and said, “All this will occur if one thinks that there is a difference between Bhagavan and oneself. If one thinks that there is no such difference, all this will not occur.”

Is it enough if we say that there is no difference between Bhagavan and ourselves? Is it not necessary to enquire who oneself is, and what one’s origin is, before one thinks that there is no difference between oneself and Bhagavan? Why is Bhagavan saying this? I was thinking of asking Bhagavan why he was thus misleading us but could not summon up enough courage to do so. I do not know if Bhagavan sensed this misgiving of mine; but anyway he himself began speaking again as follows:

I got courage as I heard those words and said unconsciously, “So there is a force?” “Yes,” replied Bhagavan, “There is a force. It is that force that is called swasphurana (consciousness of the Self).” I said with a quivering voice, “Bhagavan said casually that it is enough if we think that there is no difference between us and God. But we can discard these unreal attributes only if we are able to get hold of that force. Let it be the Divine force or the consciousness of the Self. Whatever it is, should we not know it? We are not able to know it however much we try.”

“Before one could realise that there is no difference between him and Bhagavan, one should first discard all these unreal attributes which are really not his. One cannot perceive truth unless all these qualities are discarded. There is a Divine force (Chaitanya Sakti) which is the source of all things. All these other qualities cannot be discarded unless we get hold of that force. Sadhana is required to get hold of that force.”

A lady sitting next to me told me afterwards that Bhagavan’s eyes also became moist.

Never before this did I ask Bhagavan questions in the presence of others so boldly. Today, the inner urge was so great that words came out of my mouth of their own accord in the course of the conversation, and my eyes were filled with tears and so I turned my face towards the wall. A lady sitting next to me told me afterwards that Bhagavan’s eyes also became moist. How tender-hearted he is towards the humble!

Bhagavan sometimes used to say, “The Jnani weeps with the weeping, laughs with the laughing, plays with the playful, sings with those who sing, keeping time to the song. What does he lose? His presence is like a pure, transparent mirror. It reflects our image exactly as we are. It is we that play the several parts in life and reap the fruits of our actions. How is the mirror or the stand on which it is mounted affected? Nothing affects them, as they are mere supports. The actors in this world --- the doers of all acts --- must decide for themselves what song and what action is for the welfare of the world, what is in accordance with sastras, and what is practicable.” That is what Bhagavan used to say. This is a practical illustration.

Letter 86

(86) JNANA SAMBANDHAMURTHY

Prev Next

1st February, 1947

After Bhagavan had read out from the Tamil commentary of Soundarya Lahari and told us that the words ‘dravida sisuhu’ referred to Sambandha himself, the discussion on that subject continued in the Hall for the subsequent two or three days. In this connection a devotee asked Bhagavan one day, “Sambandha’s original name was Aludaya Pillayar wasn’t it? When did he get the other name of ‘Jnana Sambandhamurthy?’ and why?”

Prev Next

1st February, 1947

After Bhagavan had read out from the Tamil commentary of Soundarya Lahari and told us that the words ‘dravida sisuhu’ referred to Sambandha himself, the discussion on that subject continued in the Hall for the subsequent two or three days. In this connection a devotee asked Bhagavan one day, “Sambandha’s original name was Aludaya Pillayar wasn’t it? When did he get the other name of ‘Jnana Sambandhamurthy?’ and why?”

Bhagavan replied, “As soon as he drank the milk given by the Goddess, Jnana Sambandha (contact with Knowledge), was established for him, and he got the name Jnana Sambandhamurthy Nayanar. That means, he became a Jnani without the usual relationship of Guru and disciple. Hence, people all over the neighbourhood began to call him by that name from that day onwards. That is the reason.” I said, “Bhagavan too acquired knowledge without the aid of a Guru in human form?” “Yes! yes! That is why Krishnayya brought out so many points of similarities between Sambandha and myself,” said Bhagavan.

“In Sri Ramana Leela it is stated, that while Sambandha was coming to Tiruvannamalai the forest tribes robbed him of his possessions. He was a man of wisdom and knowledge.

What property had he?”, I asked. “Oh! that! He followed the path of devotion, didn’t he? Therefore he had golden bells and a pearl palanquin and other symbols of that nature according to the injunctions of Ishwara. He had also a mutt (an establishment for monks) and all that a mutt requires,” said Bhagavan. “Is that so? When did he get all those?” I asked.

Bhagavan replied with a voice full of emotion, “From the time when he acquired the name of Jnana Sambandha, that is, even from his childhood, he used to sing with uninterrupted poetic flow and go on pilgrimage. He first visited a holy place called Thirukolakka, went into the temple there, sang verses in praise of the Lord, beating time with his little hands. God appreciated it and gave him a pair of golden bells for beating time. From that day onwards the golden bells were in his hands whatever he sang and wherever he went. Thereafter he visited Chidambaram and other holy places and then went to a pilgrim centre called Maranpadi.

There were no trains in those days. The presiding deity in that place observed this little boy visiting holy places on foot.

So His heart melted with pity and He created a pearl palanquin, a pearl umbrella and other accompaniments bedecked with pearls suitable for sannyasis, left them in the temple, appeared to the brahmin priests there and to Sambandha in their dreams and told the Brahmins, ‘Give them to Sambandha with proper honours,’ and told Sambandha, ‘The Brahmins will give you all these; take them.’ As they were gifts from Gods he could not refuse them. So Sambandha accepted with reverential salutations by doing pradakshina, etc. and then got into the palanquin. From that time onwards he used to go about in that palanquin wherever he went. Gradually some staff gathered around him and a mutt was established. But whenever he approached a holy place, he used to alight from the palanquin as soon as he saw the gopura (tower) of the shrine and from there onwards, he travelled on foot until he entered the place. He came here on foot from Tirukoilur as the peak of Arunagiri is visible from there.” A Tamil devotee said that that visit was not clearly mentioned in Periapuranam, to which Bhagavan replied as follows: “No. It is not in Periapuranam. But it is stated in Upamanyu’s Sivabhaktivilasam in Sanskrit. Sambandha worshipped Virateswara in Arakandanallur and won the god’s favour with his verses and then he worshipped Athulyanatheswara in the same way. From there he beheld the peak of Arunagiri and sang verses out of excess of joy and installed an image of Arunachaleswara in the same spot.

While he was seated there on a mandapam, God Arunachaleswara appeared to him first in the shape of a Jyoti (light) and then in the shape of an old brahmin.

Sambandha did not know who that old brahmin was. The brahmin had in his hand a flower basket. Unaccountably, Sambandha’s mind was attracted towards that brahmin like a magnet. He at once asked him with folded hands, ‘Where do you come from?’ ‘I have just come from Arunachalam.

My village is here, nearby,’ replied the brahmin. Sambandha asked him in surprise, ‘Arunachala! But how long ago did you come here?’ The brahmin replied indifferently ‘How long ago? Daily I come here in the morning to gather flowers to make a garland for Lord Arunachala and return there by the afternoon.’ Sambandha was surprised and said, ‘Is that so? But they said it is very far from here?’ The old brahmin said, ‘Who told you so? You can reach there in one stride.

What is there great in it?’ Having heard that, Sambandha became anxious to visit Arunachala and asked, ‘If so, can I walk there?’ The old man replied, ‘Ah! If an aged man like myself goes there and comes here daily, can’t a youth like you do it? What are you saying?’ “With great eagerness Sambandha asked, ‘Sir, if that is so, please take me also along with you,’ and started at once with all his entourage. The brahmin was going in advance and the party was following behind. Suddenly the brahmin disappeared. As the party was looking here and there, in confusion, a group of hunters surrounded them, and robbed them of the palanquin, umbrella, golden bells and all the pearls and other valuable articles, their provisions and even the clothes they were wearing. They were left with only their loin clothes. They did not know the way; it was very hot and there was no shelter, and all were hungry as it was time for taking food. What could they do? Then Sambandha prayed to God. ‘Oh! Lord, why am I being tested like this? I don’t care what happens to me, but why should these followers of mine be put to this hard test?’ On hearing those prayers, God appeared in His real form and said, ‘My son, these hunters too are my Pramatha Ganas (personal attendants).

They deprived you of all your possessions as it is best to proceed to the worship of Lord Arunachala without any show or pomp. All your belongings will be restored to you as soon as you reach there. It is noon time now. You may enjoy the feast and then proceed farther’. So saying He disappeared.

“At once, a big tent appeared on a level space nearby.

Some Brahmins came out of the tent and invited Sambandha and his party to their tent, entertained them to a feast with delicious dishes of various kinds and with chandanam (sandal paste) and thambulam (betel leaves). Sambandha who was all along entertaining others, was himself entertained by the Lord Himself. After they had rested for a while, one of the Brahmins in the tent got up and said, ‘Sir, shall we proceed to Arunagiri?’ Sambandha was extremely happy and accompanied the brahmin along with his followers. But as soon as they set out on their journey, the tent together with the people in it disappeared. While Sambandha was feeling astonished at those strange happenings, the guide who had been leading them to Arunachala disappeared as soon as they arrived there.

Suddenly, the tent along with the people in it and the hunters who had robbed them previously appeared from all sides and restored to Sambandha all his belongings which they had robbed previously, and vanished. With tears of joy, Sambandha praised the Lord for His great kindness, stayed there for some days, worshipped Him with flowers of verses and then proceeded on his journey. Out of His affection for Sambandha, who was serving Him with reverence, God Himself, it would appear, invited him to this hill.” So saying, Bhagavan assumed silence, with his heart filled with devotion and with his voice trembling with emotion.

“In Sri Ramana Leela it is stated, that while Sambandha was coming to Tiruvannamalai the forest tribes robbed him of his possessions. He was a man of wisdom and knowledge.

What property had he?”, I asked. “Oh! that! He followed the path of devotion, didn’t he? Therefore he had golden bells and a pearl palanquin and other symbols of that nature according to the injunctions of Ishwara. He had also a mutt (an establishment for monks) and all that a mutt requires,” said Bhagavan. “Is that so? When did he get all those?” I asked.

Bhagavan replied with a voice full of emotion, “From the time when he acquired the name of Jnana Sambandha, that is, even from his childhood, he used to sing with uninterrupted poetic flow and go on pilgrimage. He first visited a holy place called Thirukolakka, went into the temple there, sang verses in praise of the Lord, beating time with his little hands. God appreciated it and gave him a pair of golden bells for beating time. From that day onwards the golden bells were in his hands whatever he sang and wherever he went. Thereafter he visited Chidambaram and other holy places and then went to a pilgrim centre called Maranpadi.

There were no trains in those days. The presiding deity in that place observed this little boy visiting holy places on foot.

So His heart melted with pity and He created a pearl palanquin, a pearl umbrella and other accompaniments bedecked with pearls suitable for sannyasis, left them in the temple, appeared to the brahmin priests there and to Sambandha in their dreams and told the Brahmins, ‘Give them to Sambandha with proper honours,’ and told Sambandha, ‘The Brahmins will give you all these; take them.’ As they were gifts from Gods he could not refuse them. So Sambandha accepted with reverential salutations by doing pradakshina, etc. and then got into the palanquin. From that time onwards he used to go about in that palanquin wherever he went. Gradually some staff gathered around him and a mutt was established. But whenever he approached a holy place, he used to alight from the palanquin as soon as he saw the gopura (tower) of the shrine and from there onwards, he travelled on foot until he entered the place. He came here on foot from Tirukoilur as the peak of Arunagiri is visible from there.” A Tamil devotee said that that visit was not clearly mentioned in Periapuranam, to which Bhagavan replied as follows: “No. It is not in Periapuranam. But it is stated in Upamanyu’s Sivabhaktivilasam in Sanskrit. Sambandha worshipped Virateswara in Arakandanallur and won the god’s favour with his verses and then he worshipped Athulyanatheswara in the same way. From there he beheld the peak of Arunagiri and sang verses out of excess of joy and installed an image of Arunachaleswara in the same spot.

While he was seated there on a mandapam, God Arunachaleswara appeared to him first in the shape of a Jyoti (light) and then in the shape of an old brahmin.

Sambandha did not know who that old brahmin was. The brahmin had in his hand a flower basket. Unaccountably, Sambandha’s mind was attracted towards that brahmin like a magnet. He at once asked him with folded hands, ‘Where do you come from?’ ‘I have just come from Arunachalam.

My village is here, nearby,’ replied the brahmin. Sambandha asked him in surprise, ‘Arunachala! But how long ago did you come here?’ The brahmin replied indifferently ‘How long ago? Daily I come here in the morning to gather flowers to make a garland for Lord Arunachala and return there by the afternoon.’ Sambandha was surprised and said, ‘Is that so? But they said it is very far from here?’ The old brahmin said, ‘Who told you so? You can reach there in one stride.

What is there great in it?’ Having heard that, Sambandha became anxious to visit Arunachala and asked, ‘If so, can I walk there?’ The old man replied, ‘Ah! If an aged man like myself goes there and comes here daily, can’t a youth like you do it? What are you saying?’ “With great eagerness Sambandha asked, ‘Sir, if that is so, please take me also along with you,’ and started at once with all his entourage. The brahmin was going in advance and the party was following behind. Suddenly the brahmin disappeared. As the party was looking here and there, in confusion, a group of hunters surrounded them, and robbed them of the palanquin, umbrella, golden bells and all the pearls and other valuable articles, their provisions and even the clothes they were wearing. They were left with only their loin clothes. They did not know the way; it was very hot and there was no shelter, and all were hungry as it was time for taking food. What could they do? Then Sambandha prayed to God. ‘Oh! Lord, why am I being tested like this? I don’t care what happens to me, but why should these followers of mine be put to this hard test?’ On hearing those prayers, God appeared in His real form and said, ‘My son, these hunters too are my Pramatha Ganas (personal attendants).

They deprived you of all your possessions as it is best to proceed to the worship of Lord Arunachala without any show or pomp. All your belongings will be restored to you as soon as you reach there. It is noon time now. You may enjoy the feast and then proceed farther’. So saying He disappeared.

“At once, a big tent appeared on a level space nearby.

Some Brahmins came out of the tent and invited Sambandha and his party to their tent, entertained them to a feast with delicious dishes of various kinds and with chandanam (sandal paste) and thambulam (betel leaves). Sambandha who was all along entertaining others, was himself entertained by the Lord Himself. After they had rested for a while, one of the Brahmins in the tent got up and said, ‘Sir, shall we proceed to Arunagiri?’ Sambandha was extremely happy and accompanied the brahmin along with his followers. But as soon as they set out on their journey, the tent together with the people in it disappeared. While Sambandha was feeling astonished at those strange happenings, the guide who had been leading them to Arunachala disappeared as soon as they arrived there.